May 26, 2023

Identifying and Navigating PDA

By: Lio Riley, BA

What is PDA?

Over the past 20 years, the experience of “Pathological Demand Avoidance” has increasingly become a part of conceptualizations of neurodiversity. While initially coined “Pathological Demand Avoidance” by developmental psychologist Elizabeth Newson, many clinicians and neurodivergent individuals refer to PDA differently to describe the experience more accurately and resist pathologization (Ashwin et al., 2022; Moore, 2020; Newson, 2003). Some alternative ways people may refer to PDA include (Ashwin et al., 2022; Moore, 2020):

- Pervasive Demand Anxiety

- “Marked” or “Extreme” Demand Avoidance

- Persistent Drive for Autonomy

- Rational Demand Avoidance (RDA)

- Demand Avoidant Profile (of Autism)

- Demand Avoidance Phenomena

Individuals experiencing PDA tend to have an intense anxiety response to a perceived threat to one’s autonomy, generally resulting in a marked difficulty in completing demands for one’s self or for others (Kaye-O’Connor, 2022; PDA Society, n.d.a). Individuals with PDA may employ patterns of behavior and strategies in order to cope with and avoid such demands and the related anxiety. Often, the most obvious of these are externalized distress manifested as meltdowns.

The following have been identified as common traits of a PDA profile (Ashwin et al., 2022):

- Resists and avoids the ordinary demands of life

- Uses social strategies as part of the avoidance

- Appears sociable on the surface, but lacking depth in understanding

- Experiences excessive mood swings and impulsivity

- ‘Obsessive’ behavior, often focused on other people

- Appears comfortable in role play and pretend play, sometimes to an extreme extent (this feature is not always present)

In addition to the most commonly recognized behavioral presentations of PDA, individuals who describe their experience as “internalized PDA” have also shared possible behavioral differences discussed in greater detail below. Behavioral demand avoidance is significant, but it is “not the only trait in a PDA profile” (PDA Society, n.d.a.). While behaviors can vary from person to person, intense anxiety and distress related to demands is a key experiential factor of PDA.

Currently, PDA is not a formal diagnosis recognized in the DSM-5 or the ICD-10 (Kaye-O’Connor, 2022). However, it is recognized by many professionals as a significant cluster of traits. In the UK and Australia, PDA tends to be recognized more formally, often by noting it alongside a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder as one would note a specifier or including it in a report (PDA North America, 2023). In the United States, PDA seems to be less often recognized by professionals, instead identified by individuals or their families and caretakers. For this reason, while some healthcare professionals in the US are gaining familiarity with PDA, it is less likely to be first recognized by a provider. Recognizing PDA can be important for informing parenting approaches, strategies for navigating distress, and treatment considerations, so people who suspect that they or their child is PDA could benefit from understanding the profile and commonly-used strategies to manage resulting anxiety.

For more information about the nuances of identifying PDA, visit the PDA Society’s resource on “Identifying and Assessing PDA” (Ashwin et al., 2022).

PDA, Autism, and Neurodiversity

PDA is currently thought to be associated with autism, but this has not always been the case. PDA was conceptually developed in response to a group of patients with an “atypical autism” diagnosis that “didn’t make sense” to the parents and professionals around them (Newson et al., 2003). Notably, this group was mostly girls who were more “social” and “passive” than their (mostly male) counterparts with a typical ASD diagnosis. At the time, this was taken as evidence that PDA must be a separate condition from autism, because it was believed that autism in girls was relatively rare.

Over the past 20 years, we’ve come to understand that autism is not as rare in girls as was once believed, but may present differently (Maenner et al., 2021; Ratto et al., 2018). Therefore, many believe PDA is actually closely related to autism rather than a mutually exclusive category (Ashwin et al., 2022). In most contemporary research and conversation, PDA is generally considered to be either a sub-profile of autism or a commonly co-occurring condition (Kildahl et al., 2021).

Allison Moore (2020) explores PDA through the lens of autism to explore the ways in which the demand avoidance may not be inherently “pathological” as it is perceived by others. She points out that “when the demands of everyday life produce considerable and debilitating anxieties, their avoidance is best understood not as pathological but as entirely reasonable and, indeed, rational” (p. 43) When Autistic individuals experience the world in a fundamentally different way than allistic people, it makes sense that they might “go to great lengths to avoid coming into contact with things that produce distress,” even if these things might not be experienced as distressing by allistic people (Moore, 2020, p. 43).

What are “Demands”?

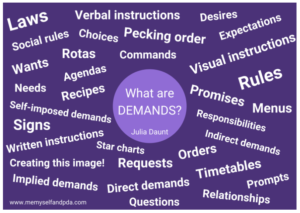

Often when people with PDA are described as “demand-avoidant,” people tend to think of demands as being requests or instructions to complete a certain action, generally issued by a person with an authority status like a parent, teacher, or boss. While PDA folks certainly do experience anxiety related to these kinds of demands, considering only external, direct demands offers a limited perspective of what “demands” are. In addition to direct demands, PDA folks have explained various other types of demands that lead to similar anxiety. Some other types of demands include the following (PDA Society, n.d.a):

- Internal demands: things like hunger, thirst, using the restroom, and similar bodily needs.

- Uncertainty: uncertainty can prompt feelings of not being in control, triggering demand avoidance.

- Praise: can carry an ‘implied expectation’ that a behavior should be performed the same way again in the future.

- Time Constraints and Scheduled Events: places pressure on how long a person has to complete a task or uphold a previously-made commitment.

- Making Decisions: knowing that a decision must be made can trigger demand avoidance.

Various types of “demands” as listed by Julia Daunt, a PDA adult and advocate (PDA Society, n.d.a).

All PDA individuals will experience demands differently, so what might trigger anxiety for one person might decrease anxiety for another. For example, while ‘decisions’ is listed above as a possible type of ‘demand,’ many PDA folks can feel less anxiety when they’re offered choices, as it can offer an opportunity for autonomy. Each person will have different experiences, so learn what strategies work the best for you/your loved one!

Internalized PDA

Frequently, PDA is identified by the recognition of externalized manifestations of demand avoidance, such as outbursts, refusal, or dysregulation. However, many PDA individuals have begun sharing about internalized experiences and manifestations of PDA, which may make it more challenging to identify. Internalized PDA experiences could include becoming more quiet or withdrawn when triggered; using social strategies to avoid demands; becoming perfectionistic or complying more than might be expected; and struggling with self-advocacy (Cat, 2022; Kildahl et al., 2021).

One individual who’s shared their experience with internalized PDA explains that internalizing the distress does not make it “milder” than in those with externalized manifestations of PDA (Cat, 2022). Instead, the intensity of the anxiety is just hidden from the view of others. Therefore, people with internalized PDA might be less likely to have their struggles identified or validated, leaving them susceptible to many of the same challenges without much support.

The internalization of demand anxiety may reflect a recently-coined stressor and trauma response referred to as “fawn.” Rather than one of the familiar fight/flight/freeze responses, someone who responds to a stressor with a fawn response may forgo their own needs in order to appease those around them and avoid conflict (Ryder, 2022; Taylor, 2022). Fawning “[responds] to a threat by becoming more appealing to the threat,” as if the “price of admission to any relationship is the forfeiture of all their needs, rights, preferences, and boundaries” (Walker, 2013 as cited in Ryder, 2022). PDA children who respond to demands with a fawn response may comply with the demand, sometimes even exceeding expectations, to maintain a sense of security in their relationships. While their compliance may be convenient for adults in the scenario, the child’s internal distress remains unaddressed.

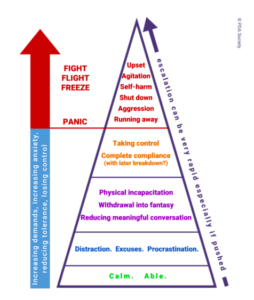

A graphic depicting varying levels of escalation a PDA person may experience (PDA Society, n.d.a).

PDA Strategies

PDA individuals and their communities often describe approaches to managing PDA-related distress as “PDA strategies” (Russell, 2018). These approaches are largely developed within the community itself, as traditional approaches to anxiety like cognitive behavioral therapy have not been as successful (Russell, 2018). Generally, PDA strategies work to offer autonomy to PDA individuals and minimize unnecessary demands. Below are some common strategies used to navigate PDA-related distress. These are primarily focused on parents or other caregivers interacting with children, but can be adapted for individuals across the lifespan. Finally, while the strategies below have been beneficial for many, every PDA individual will have different experiences of demands and related needs. It’s important to maintain a flexible approach that best meets the needs of the individual rather than assuming PDA strategies will always be successful.

PANDA Approach

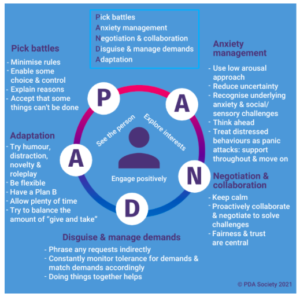

One approach to communicating with PDA children that has been helpful for some parents is the “PANDA” approach (PDA Society, n.d.a.; PDA Society, n.d.b.; Samantha, 2021). “PANDA” stands for the following:

- Pick battles

- Anxiety management

- Negotiation and collaboration

- Disguise and manage demands

- Adaptation

Below are a description of each of the approaches, as well as an example of how it may be used (PDA Society, n.d.a.; PDA Society, n.d.b.; Samantha, 2021):

Pick battles: Parents can cut back on their child’s cumulative stress by reducing demands that are not necessary. Additionally, it may help parents to be more intentional about how often they are issuing demands. A child may resist a demand that a parent hadn’t even realized was a demand to begin with. In circumstances like these, parents can consider the necessity of such a demand and change their approach accordingly. Finally, when demands are necessary, parents can offer their children choices when demands are necessary to increase autonomy.

Example: A child regularly resists brushing their teeth at night. The parent knows that this is important for their health, but also understands that fighting may cause more resistance, so they opt for a more flexible approach. The parent allows the child to determine the order of the steps in their bedtime routine to allow for some autonomy. They also keep a few flavors of toothpaste in the bathroom to incorporate a fun choice into the task. In doing so, they can support their child’s health without an unnecessary ‘battle,’ and the child develops valuable independence and self-care skills.

Anxiety management: some research has indicated that feelings of uncertainty may underlie demand-related anxiety (Stuart et al., 2019). To mitigate this, parents can reduce uncertainty to reduce the feeling of a ‘demand.’ Providing explanations for necessary demands could also reduce uncertainty about the reason behind the demand. Finally, thinking ahead about sensory or transition-related challenges can prevent demand-related anxiety (PDA Society, n.d.b.).

Example: A parent is making dinner reservations for their partner’s birthday and realizes the restaurant is one they have not yet taken their child to. They print out the restaurant’s menu; photos of the interior; and the restaurant’s location on a map for their child to explore in advance. This allows the child to choose a meal beforehand to manage decision-related anxiety, as well as reducing uncertainty about the environment in the restaurant. On the day of, the parent brings the child’s noise-canceling headphones to make sure they are prepared for any sensory-related distress.

Negotiation and collaboration: This strategy relates closely to “pick battles” and allows for middle-ground. In instances where a demand may not be necessary, but is important or unavoidable, parents can partner with their children to provide a supportive, communicative approach to the situation. The benefit of this approach is twofold, as it both reduces uncertainty about the demand and offers choice to the child. It also places the child and parent on the same “team” rather than in opposition to one another. This strategy is most successful when demands are negotiated in advance, as a child may be too dysregulated in the moment an unexpected demand is placed to communicate openly and thoughtfully (PDA Society, n.d.b). It’s important to note that for this to be successful, adults need to be willing to compromise as well.

Example: The child arrives at their soccer game — their favorite extracurricular — but is experiencing distress about being required to play and states that they want to quit. Understanding that this is related to demand anxiety (rather than the child simply disliking soccer), the parent, child, and coach discuss the situation, and decide together that the child will play as an ‘alternate’ this weekend and let the coach know when they feel ready to go in. This solution allows the child to continue participating in their favorite sport while managing an acutely distressing moment in time.

Disguise and manage demands: Making demands indirectly can often manage anxiety about them, especially if they aren’t necessary, urgent, or need to be done in a specific way. Using declarative language (see below) rather than imperative language can reduce the feeling of a demand by allowing the child to choose to act on what has been said. Demands can also be ‘disguised’ by incorporating choices, limiting expectations, and modeling behavior. Finally, monitoring the child’s demand anxiety throughout the day can help determine when demands might need extra ‘disguising’ or minimizing.

Example: One parent noticed that their child would return home from school with a water bottle still full from the morning, but that suggesting or asking them to drink water caused even more resistance (Samantha, 2021). The parent instead filled the water bottle up only halfway, which made the child feel less of an expectation to drink all of the water. This parent ‘disguised’ the demand of drinking water, which helped the child accomplish a necessary task without perceiving pressure from themself or others.

Adaptation: Finally, while it’s possible to manage demand anxiety using a variety of strategies, adaptability will often be necessary for moments when strategies don’t work. Maintaining flexibility in tough situations can make it easier for yourself and the child to move through the situation. Using a sense of humor, distraction, novelty, and roleplay may help. For time-sensitive demands, incorporating extra time up front can prevent ongoing struggles over lateness. Finally, having a back-up plan can make adapting feel less stressful and spontaneous when it needs to happen.

Example: A child is getting ready to attend their sibling’s choir concert, but is feeling overwhelmed by the impending demand of sitting quietly in an auditorium. Their parent brings along another adult friend who, if needed, could bring the child into the lobby as a “Plan B” so that the parent doesn’t miss the performance of their other child. Additionally, the parent brings a coloring book full of their child’s favorite characters as a “distraction” technique. Having something calming to do, as well as knowing there’s an option to leave the room if needed, allows the child to stay regulated throughout the concert and enjoy the music by minimizing the demands.

The “PANDA” strategy can support caregivers in meeting the needs of PDA children (PDA Society, n.d.b.).

Declarative vs Imperative Language

In addition to employing strategies to manage demand-related anxiety and offering opportunities for autonomy, adjusting one’s communication style to remove hidden demands or re-frame demands can also help prevent distress.

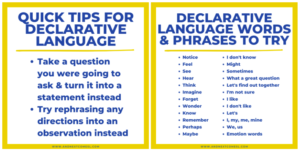

For PDA individuals, declarative language seems to be less likely to induce demand-related anxiety than imperative language. Imperative language demands a response (Journeys with PDA, 2023). This includes direct statements with an expected action to perform, as well as questions that require the individual to respond (Journeys with PDA, 2023). On the other hand, declarative language does not imply a correct or expected response, but instead “share(s) information which then invites the [person] to engage on their own terms” (The Childhood Collective, 2021). It’s important to note that declarative language is not meant to be passive-aggressive or to heavily imply what imperative language might state directly. Shifting language without shifting underlying relational dynamics of communication may not have the same beneficial impact. Therefore, parents attempting to integrate more declarative language should be mindful of their tone of voice and implicit expectations when using it.

Some examples of imperative language and potential declarative alternatives are listed below:

| Imperative Language | Declarative Alternative |

| Go grab a pencil so I can help with your math. | I think we need some pencils to get started. |

| Use your words. | I feel confused because I’m not sure what you mean by that. |

| Get your backpack on so we can leave. | I’m going to go start the car so we can leave for school. |

| What did you think about the movie? | My favorite part of the movie was _____! I noticed you were laughing at that part, too. |

| How was your day today? | I’m wondering what was going on at school today! |

The key difference between imperative and declarative language is that the latter gives individuals flexibility in how they choose to respond. While it may not be possible to avoid imperative language altogether, declarative language has many benefits for children beyond experiences of PDA. The use of “I” statements allows children to “hear the thoughts” of the caregiver, which can support language development and self-regulation as they develop their own “inner voice” (The Childhood Collective, 2021). It also encourages children to become more thoughtful about their responsibilities in the household and the community by giving them opportunities to engage with the responsibilities on their own terms rather than complying simply because they are “supposed to.” Finally, it can support the development of secure attachment in their relationships. The child can become more familiar with regularly encountering the perspectives and thoughts of others, and will likely feel more empowered to share their own perspectives and thoughts, as well (The Childhood Collective, 2021).

Quick tips and examples of declarative language phrasing from https://www.andnextcomesl.com/2022/05/what-is-declarative-language.html (Robson, n.d.).

In addition to declarative language, the PDA Society (n.d.b.) provides a list of alternative communication approaches that may also be effective for PDA individuals.

Summary/Conclusion

While our understanding of PDA is still in its early stages, the experience has been resonant with countless children, families, and individuals. It’s imperative to understand the underlying anxiety that leads to demand avoidance in order to best support individuals experiencing it. By adjusting communication and parenting approaches, it’s possible to help young people with PDA navigate their demand-related anxiety.

Recommended Reading and Resources

Books for Grown-Ups:

Declarative Language Handbook and Co-Regulation Handbook by Linda K. Murphy

Cool, Calm & Connected: A Workbook for Parents and Children to Co-regulate, Manage Big Emotions & Build Stronger Bonds by Martha Straus

Life on an Alien Planet: Pathological Demand Avoidance: A PDA boy and his journey through the education system by Katie Scott

The Explosive Child by Ross Greene

Beyond Behaviors: Using Brain Science and Compassion to Understand and Solve Children’s Behavioral Challenges by Mona Delahooke

Brain-Body Parenting: How to Stop Managing Behavior and Start Raising Joyful, Resilient Kids by Mona Delahooke

The Teacher’s Introduction to Pathological Demand Avoidance by Clare Truman

PDA in the Therapy Room by Raelene Dundon

PDA by PDAers: From Anxiety to Avoidance and Masking to Meltdowns by Sally Cat

Books for Young Readers:

*Super Shamlal: Living and Learning with Pathological Demand Avoidance by Kay Al-Ghani and illustrated by Haitham Al-Ghani

Pretty Darn Awesome: Divergent not Deficient: Understanding Pathological Demand Avoidance on the Autism Spectrum by Lauren O’Grady

The Panda on PDA: A Children’s Introduction to Pathological Demand Avoidance by Gloria Dura-vila and illustrated by Rebecca Tatternorth

I’m Not Upside Down, I’m Downside Up by Harry Thompson and Danielle Jata-Hall

It’s a PanDA thing – A visit to the World of PDA by Rachel Jackson and Zeke Clough

Poppy and the Overactive Amygdala by Holly Rae Provan and illustrated by Eric Provan

Me and My PDA: A Guide to Pathological Demand Avoidance for Young People by Glòria Durà-Vilà and Tamar Levi; illustrated by Tamar Levi

Listening to My Body by Gabi Garcia

Websites:

PDA Parents (Michigan-based!)

Podcasts:

Fight and Fawn hosted by Kristy Forbes and FAN

PDA Parents hosted by Caitie and Casey

References

Ashwin, K., Buchan, L., Doyle, A., Dundon, R., Glew, S., Gullon-Scott F., Howell, C., Jones, J., Kerbey, K., Kidd, T., Laing, K., Marsden, A., Muniz, M., Philip, J., Soppitt, R., & Truter, B. (2022, January). Identifying & Assessing a PDA Profile — Practice Guidance. PDA Society. https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/what-is-pda-menu/identifying-assessing-pda/

Cat, S. (2022, April 16). Internalized PDA – the quieter, but equally impactful presentation of PDA that’s hard for people to spot. Sally Cat PDA. http://www.sallycatpda.co.uk/

The Childhood Collective. (October 15, 2021). Help Your Child Self-Regulate by Using Declarative Language. The Childhood Collective Blog. https://thechildhoodcollective.com/2021/10/15/help-your-child-self-regulate-with-declarative-language/

Journeys with PDA. (2023). Declarative Language. Journeys with PDA: Our Journeys of Unwavering Faith and Unconditional Love. https://irp.cdn-website.com/a474242a/files/uploaded/Declarative%20Language%20for%20PDA.pdf

Kaye-O’Connor, S. (2022, October 11). Pathological Demand Avoidance: Characteristics & Treatments. Choosing Therapy. https://www.choosingtherapy.com/pathological-demand-avoidance/

Kildahl, A., Helverschou, S., Rysstad, A., Wigaard, E., Hellerud, J., Ludvigsen, L., & Howlin, P. (2021). Pathological Demand Avoidance in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Autism, 25(8), 2162-2176.

Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 2021;70(No. SS-11):1–16. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1external icon

Moore, A. (2020). Pathological demand avoidance: What and who are being pathologised and in whose interests? Global Studies of Childhood, 10(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619890070

Newson, E., Le Maréchal, K., & David, C. (2003). Pathological demand avoidance syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(7), 595-600.

PDA North America. (2023). PDA North America: Support & Resources for Individuals & Families Living with Pathological Demand Avoidance. https://www.pdanorthamerica.com/

PDA Society. (n.d.a). What is Demand Avoidance? PDA Society. https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/what-is-pda-menu/what-is-demand-avoidance/

PDA Society. (n.d.b.). Helpful Approaches for Parents and Carers. PDA Society. https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/life-with-pda-menu/family-life-intro/helpful-approaches-children/

PDA Society. (n.d.c.). Helpful Approaches with PDA — Children. PDA Society. https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Helpful-approaches-for-parents-and-carers.pdf

Ratto AB, Kenworthy L, Yerys BE, Bascom J, Wieckowski AT, White SW, Wallace GL, Pugliese C, Schultz RT, Ollendick TH, Scarpa A, Seese S, Register-Brown K, Martin A, & Anthony LG. (2018). What About the Girls? Sex-Based Differences in Autistic Traits and Adaptive Skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1698-1711. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3413-9. PMID: 29204929; PMCID: PMC5925757

Robson, D. (n.d.) What is Declarative Language and Why Should You Use it? And Next Comes L. https://www.andnextcomesl.com/2022/05/what-is-declarative-language.html

Russell, S. (2018). Being Misunderstood: Experiences of the Pathological Demand Avoidance Profile of ASD. The PDA Society. https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/BeingMisunderstood.pdf

Ryder, G. (Jan 9, 2022). The Fawn Response: How Trauma Can Lead to People-Pleasing. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/health/fawn-response

Samantha. (March 22, 2021). How to use the PDA PANDA Support Strategies. Support Essentials. https://supportessentials.com.au/pda-panda-support-strategies/

Stuart, L., Grahame, V., Honey, E., & Freeston, M. (2019). Intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety as explanatory frameworks for extreme demand avoidance in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 25(2), 59-67.

Taylor, Martin. (2022, April 28). What Does Fight, Flight, Freeze, Fawn Mean? WedMD. https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/what-does-fight-flight-freeze-fawn-mean